A League of Kings: For Roma, By Roma

24 December 2024

This interview comes from the anti-racist fanzine ‘A Sporting Chance’, created by the ERRC in 2024 to highlight the experiences of Roma, Sinti, & Travellers fighting racism through sport as part of the EU-funded Moving On project.

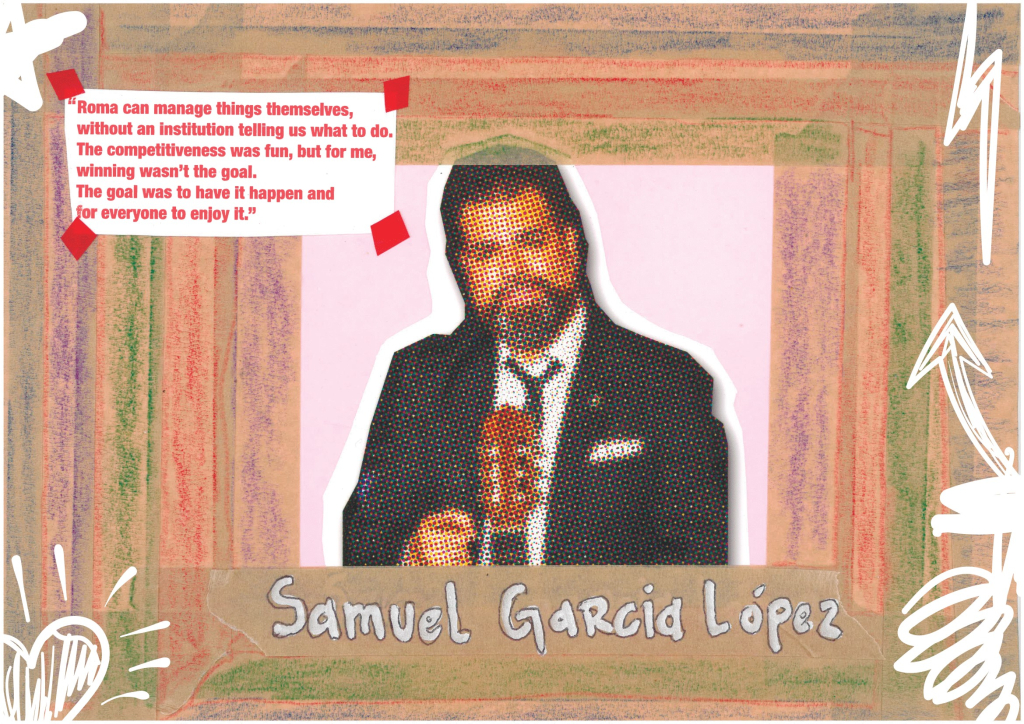

We caught up with Samuel García López, one of the founders of the ‘Gypsy King’s League’ which was created by Romani communities in Barcelona seeking to emulate Gerard Piqué’s celebrated viral football league.

Piqué’s original ‘King’s League’ started in Barcelona in 2022 and blends online streaming and gaming elements with a futsal style, seven-a-side game. The league features unconventional football rules such as unlimited substitutions, penalty tiebreakers, and ‘secret weapons’ & ‘wild cards’ which allow teams special plays such as: an automatic penalty, the ability to suspend an opposing player for four minutes, or to nominate ‘star player’ whose goals count as double for a period. The Gypsy Kings League now has teams from across Spain competing in an entirely Roma-made sports league that Samuel can be proud of.

So firstly, what is the situation like for Romani people in your city?

It depends on each neighbourhood, and it depends on the family context, right? Some people are better off, while others...There is the part of the city of Barcelona where we are more rooted, and then there are other areas on the outskirts, which might be worse off. But, well, there are also Roma in central Barcelona who are struggling. It’s not all the same, you know?

I am from El Raval. I’ve lived here all my life, and I consider myself from here, but I come from El Poble Sec which is nearby. There’s no border between El Poble Sec, Sant Antoni, and El Raval. There is a large Romani population in El Poble Sec and Sant Antoni. Most of them used to live here in El Raval but since the 1990s, due to gentrification, they moved and now most live in El Poble Sec and Sant Antoni.

I'd like to understand more about what work do you do within the Romani community?

Well... I work a lot with music, specifically Catalan rumba, with theatre, with very artistic projects, and also with the recovery of Romani memory. Those are my strengths. That’s why I created the Barcelona Urban Roma Eco-Museum, which is the first of its kind. An eco-museum is a different concept from a traditional museum. A museum typically has exhibitions of artists, right? Visitors, an institution that manages it, right? An eco-museum involves three things: a territory, a heritage, and a community. In the eco-museum, it is the community that sustains it. And how do they sustain it? With their heritage: their stories, photos, objects, and donations made by the community.

Great. So, do you create projects with them, or do you showcase Romani culture and traditions for others within the Romani community itself?

Well, I do create projects, but there are also projects that come from the community. Then I try to carry them out. For example, the "Gypsy King's League" right? The young people came to me wanting to create it.

How did it start? Tell us a little about it.

I’ve always wanted to do something related to football... something, you know? So, we had some barbecues and organised some games, and that’s how the idea of the King’s League came about. Some young guys, José and Joni, came to me and said, “We could do something like the King’s League.” I said, “Great, let’s do it.” I called a few Roma associations in Barcelona, and we started with friendly matches. Initially, I just wanted friendly games. But then I made an agreement with the Satalia football field. They gave us a reduced price to organize a pre-league. We did a pre-league with people from the neighbourhood, mainly to unite the neighbourhood and foster connection after the pandemic, because people had become more distant. We started with four teams: Soniquetes, Gipsy Julians, and... I can’t remember the others. Two more teams. Then we brought in boys from Zona Franca, Hostafrancs, and Gràcia, and they all came together for the pre-league. The second game was recorded and uploaded to TikTok, and it went viral.

From there, things grew because players would ask well-known artists or strong players they knew to make videos, and the project just kept getting bigger. YouTubers who were with us commented on and reacted to our games, saying ours were better than theirs! So it went even more viral. Eventually, I contacted El Periódico, and that really blew things up. The headline was, “We want to play a match with Piqué.” From there, things escalated even more. Piqué invited us to his league; we had good chemistry with him. And this is all from a youth initiative led by young Roma.

How did it go from being a casual weekend game to a fully-fledged project, including financing?

We didn’t have any funding. Zero. Everything we did, we paid for ourselves: the equipment, the fields, the referees, the TikTok people, the cameras, everything was paid by us and the players.

Have you tried to secure funding for the project?

I applied for a grant from the city council to cover the cost of the fields and the equipment. I don’t remember exactly if I asked for 3,000 or 4,000 euros. In the end, they approved 1,000 euros, but I would have had to justify expenses of 4,000 or 5,000 euros, which meant putting in 3,000 from my own pocket. So, I had to give up the 1,000 euros. I said, "If I need to spend 3,000 to get 1,000, I’m not going to bother." So, I declined it and said we’d continue as we’ve been doing, paying for everything ourselves. That’s how it’s been.

How do you organise something this big with no institutional support?

There were three presidents: one was in charge of organising the matches, another was responsible for the institutional relations with associations and managing the fields, and the other handled relations with the teams. I created a form for all the players to register, with questions and regulations. We went neighbourhood by neighbourhood explaining the rules and registering players. We held a pre-league, which exploded in popularity. Then, everyone wanted to play. At one point, we were getting calls from Melilla, Madrid, Bilbao, and Valencia from people wanting to play. How do we cover the costs? Even Mallorca had a team that flew in for every game. They paid their own way, and that’s how it’s been.

Why did you take on such a big challenge? What made you say, "This needs to happen"?

Because I saw it very clearly... I wanted to do something in sports, and there’s always been this stereotype that Roma don’t do sports, that we’re all overweight. It was a personal challenge to prove otherwise. I knew it would go viral. I was certain. I woke up a whole part of Spain that no one else has. Other leagues have sprung up from ours, like the King’s League in Madrid and Bilbao. For me, that’s a win. Promoting sports and seeing people do it because of my project—money doesn’t matter. I wanted to do this for free, and it has now even inspired other Roma to create women’s teams.

Has a ‘Queen’s League’ been created?

Not yet, but women's teams have started playing friendlies in Zona Franca, La Mina, and other areas. This could become a future project.

What are the most important values or lessons that you think have been promoted through this project?

The biggest takeaway for me is that Roma can manage things themselves, without an institution telling us what to do. The competitiveness was fun, but for me, winning wasn’t the goal. The goal was to have it happen and for everyone to enjoy it. The project also became a way to fight against anti-Roma sentiment through positive projects. Instead of focusing on our historical struggles, which are important not to forget, but it’s time to change the narrative through positive actions.