Roma Purged from World Cup as Moscow Undergoes ‘Clean-up’

17 July 2018

Moscow – On a cool, cloudy day in the north of Moscow, sixteen homeless people and twelve volunteers came together in Sokolniki Park to play football. They were there to take part in the Homeless Football Championship, a one day event organised by the charity Miloserdie, just five days before the world’s greatest sporting event was set to arrive in the capital. According to the tournament organizer, Irina Mesherekova, the event was organised to show that “football is a game for everyone.”

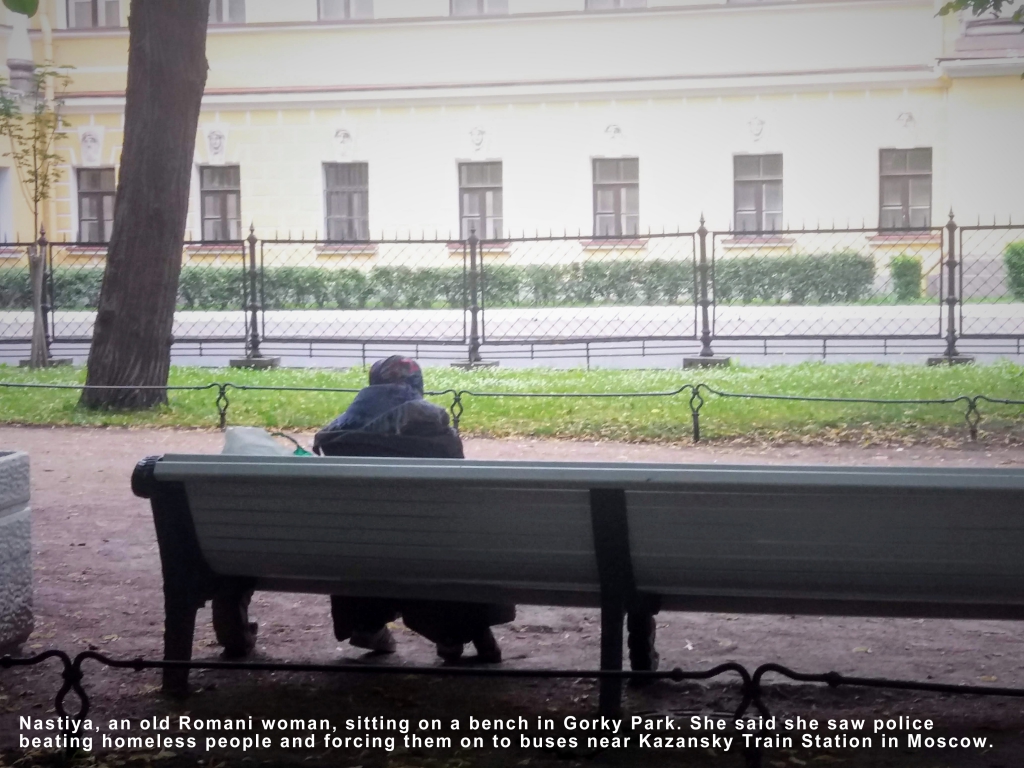

At the same time, preparations of different kind were underway across the city in the run up to the 2018 FIFA World Cup. Moscow’s underclass - those persons deemed undesirable by the authorities, made up mostly of the homeless and Roma - were being quietly removed from the streets through harassment, forced eviction, and expulsion from the city limits.

Roma found by police without identification papers were swept out of the city along with the homeless population. They were sent by bus, sometimes over 100km away, to specially designated camps outside of the city for the duration of the tournament. Those who refused, were sent by force.

“The police always say to go, its normal. But I know many were taken away from here on the buses” said 22-year-old Luciya, a Romani woman begging in the city centre near Moscow’s Cathedral of Christ the Saviour. “We saw buses with many people on them at night and police everywhere, near Paveletsky [train station]. They can do anything to you: beat you, put you in jail, take your child, there is nothing you can do about it.”

Luciya knows all about the terror which the city police wield over the city’s vulnerable inhabitants. Most Roma she knows have been either removed from the city centre or threatened by police to stay away during the tournament. She risks a lot in coming to the centre and begging in an area where she will be visible to tourists, alongside her 30-year-old sister-in-law, Dina, and 25-year-old friend Maria.

“There are much more police now in the city, so we have to watch for them always. Sometimes they take us to the police station and keep us there for a few hours, then they let us go. This is normal, even though we have done nothing wrong” says Luciya.

Her friend Maria adds “I know people who have had their children taken because they did not have the right identification, or it was not their child, it was their friends’ or sisters’ or something.” Luciya agrees and says: “Some of us have no identification papers, so they can do anything. This is why I have my child here so they can’t take us away.”

Lack of documentation is a common reason for police to arrest, harass or even deport Roma in Moscow. In Luciya’s case, the problems she faces now stem almost entirely from her lack of identification documents.

Born in Moldova, she came to Russia when she was very young when her Russian father came looking for work. As wages stagnated and unemployment began to rise, her family found themselves without regular work and their situation became ever more precarious, until they were forced to leave their home and live in temporary shelters, squats and barracks. Her parents’ Soviet Union internal passports became invalid in 1997, but due to their lack of permanent address and the complex bureaucracy which made registration an onerous process, they never received a Russian internal passport before the 2004 deadline. Luciya’s inherited lack of documentation has meant that she was unable to register her one-year-old son, Dimitry, and lives in fear of authorities taking him away from her when she is stopped by police.

According to a research project carried out by the European Roma Rights Centre, European Network on Statelessness, and Institute on Statelessness and Inclusion: lack of identification documents is form of structural discrimination which affects Roma all across Eastern Europe. Lack of ID opens Roma up to further discrimination in access to healthcare, schooling, employment and social assistance, as well as making them easy targets for state violence.

In Russia, police officers can use a lack of identification documents as a pretext for further action to remove Roma from Moscow during the World Cup. However, even Roma with their papers in order are being threatened and warned away. Luciya’s 25-year-old husband Aleksander is a Russian citizen with a valid ID. He normally earns a living by collecting scrap materials and buying and selling used items to traders at Moscow’s street markets. Now according to Luciya, he cannot show his face in areas of the city where he would normally try to find work.

“If you are Roma man, they tell you to stay away from centre while the football happens, so now they cannot work. They stay at home because there is no work because of the football. They cannot work because of police” she says, while preparing dinner for her family back at their home in a shared barrack in the Yasenevo district on the edge of the city.

Their makeshift kitchen is a gas-burner in a damp, concrete corner of the barrack with plastic tarpaulin covering the window opening. Family and friends recline on armchairs and mattresses outside and drink tea while Aleksander talks about the measures Moscow’s finest take to ensure a Roma-free World Cup.

“They [the police] want to make the city good for the tourists…it looks shameful for them to see Gypsies there. Also they know the look of our faces, when my wife is begging they come later to here to get revenge” he says. “They have no shame. It is not enough [for them] that we are forced from the city, they come here too and beat us, ask for papers, say they will take our children.” As if to emphasise his point, six police officers arrived some time later on the street outside and began to aggressively interrogate the Roma: separating the men from the women, and demanding identification with hands gripping the truncheons at their waist. It was only on the production of a ‘FIFA Fan ID’ and the presence of a foreigner in their midst that the officers stood down and left them alone for the evening (after fist accusing the Roma of kidnapping a tourist).

Sergey Mikheyev from the human rights organisation, Anti-Discrimination Centre ‘Memorial’ (ADC ‘Memorial’), says that xenophobic and racist attitudes have increased in Russia in recent years, and with this, so have the number of arbitrary actions of Russian police officers aimed against Romani people. Sergey reported “cruel treatment during detentions and placement in detention centers, arson of Roma houses, special police raids branded “Roma” and “Roma Settlement” which were held in various locations in Russia, often involving ‘volunteers’.” The situation for Roma in Russia is worse than it has been in many years. ADC ‘Memorial’ describe a litany of rights violations carried out against Roma in Russia by state authorities in a report delivered by the United Nations, including “deprivation of access to resources (water, gas, electricity), demolitions of houses and forced evictions of Roma, including children, and often in winter; segregation of Roma children in so-called “Gypsy classes” and even in “Gypsy schools”, very bad education that doesn’t allow children to enter secondary school; lack of state programs on overcoming structural discrimination of Roma, and repressive anti-Roma practices all over Russia.”

Luciya and Aleksander must deal with these daily hardships of institutional discrimination and antigypsyism. The World Cup has only brought them and others like them additional problems, as well as the momentary attention of the state security apparatus, something no one wants in Russia.

The arrival of FIFA’s festival of football in Moscow has brought with it a deceiving air of tolerance to the city. Rainbow LGBT flags are beginning to (if only hesitantly) appear in public places, police pose for selfies with football fans from across the globe, and the ordinarily strict prohibition on public disorder has given way to a carnival of drunken revelry on the streets of the capital. The dating app ‘Tinder’ has even seen a sixty-six percent increase in matches, clustered around the eleven host cities of the World Cup which have attracted over two million international visitors. The festivities have come at a price though, and often it is Roma who are the ones losing out to the tournament. The police measures to remove ‘undesirables’ from the city centre has compounded the discrimination already keenly felt by the country’s most marginalised ethnic minority. It remains to be seen what the aftereffects of this world cup will be in terms of a response from the state. Fears of a broad spectrum crackdown on civil society, activists and minorities once the attention of the world turns elsewhere are not exaggerated. Roma can only hope that after the crowds leave the capital and the inevitable post-world cup hangover kicks in, they will pass under the radar and try and resume their lives.

The Ministry of Internal Affairs was contacted for comment on the removal of Roma and homeless people from Moscow, as well as the violence, threats, and harassment by police officers towards Romani women. They had not responded at the time of writing this article.

The names of people and sometimes places mentioned in this article have been changed to protect the identities of the Roma who agreed to be interviewed.

(This article was originally published in the "Travellers’ Times")