Rukeli: One of the Greatest of All Time

20 December 2024

By Jonathan Lee

This article comes from the anti-racist fanzine ‘A Sporting Chance’, created by the ERRC in 2024 to highlight the experiences of Roma, Sinti, & Travellers fighting racism through sport as part of the EU-funded Moving On project.

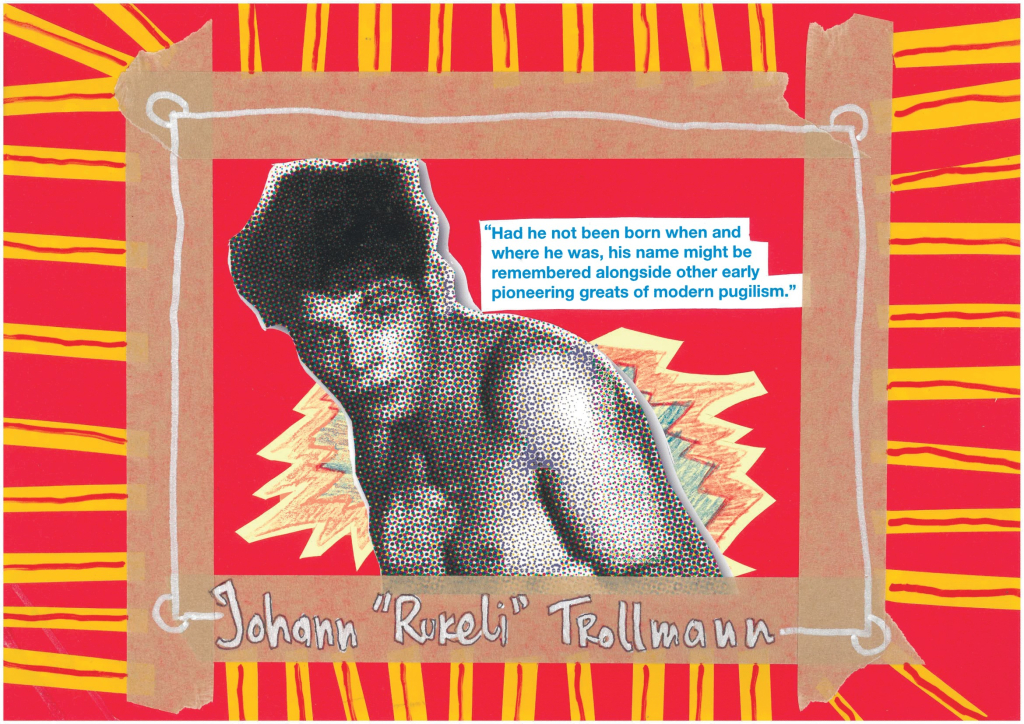

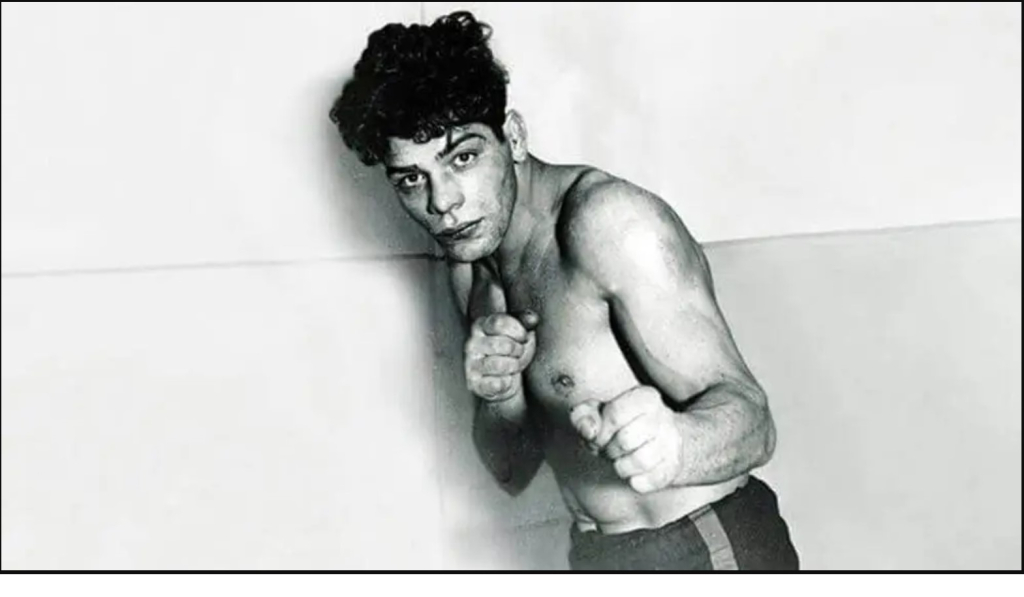

The boxer whose image is on the front cover of this fanzine is a Sinto man named Johann ‘Rukeli’ Trollmann.

Rukeli the Symbol of Defiance

Born in 1907 near Hannover, he was nicknamed ‘Rukeli’ because his athletic stature reminded family and friends of a strong tree (ruk in the Romani language). In 1933, he became the German light-heavyweight champion by defeating the all-Aryan-favoured contender Adolf Witt. He was stripped of his title eight days later for his ethnicity and his defiance in the face of the Nazis.

Despite being robbed of the title, Rukeli was still the darling of the boxing public. Good-looking, and with fast ‘dancing’ footwork, the papers called him ‘the Gypsy in the ring.’ Everything he was represented a threat to the notion of Aryan physical superiority. So, the day before his next fight against the big-hitter, Gustav Eder, the Boxing Union threatened to remove his boxing license if he did not drop his decidedly un-German fighting style. Despite knowing that he could never win a fight trading punches toe-to-toe with Eder, Rukeli turned up to fight anyway. To the scandal of the Nazi world, he arrived in the ring with his hair dyed blond, and his face and body whitened with flour in a grimly comic parody of Aryan purity. Rukeli stood bolt-upright in the middle of the ring, feet planted stationary in the ‘German style’ and took the blows for four rounds before being finally knocked out in the fifth.

Rukeli was told that a ‘gypsy’ would never be allowed to be champion in Germany. He continued boxing but was now the national villain of the boxing press and the boxing union and couldn’t train in boxing gyms. After being forced to change his modern fighting style in favour of the plodding and predictable style derived from bareknuckle prize fighting, Rukeli only won one of the remaining 11 bouts of his career. In a final ‘fuck you’ to the Nazis who took his title, he allegedly turned up for his final fight dressed in the ‘Brownshirt’ paramilitary uniform of the SA (Sturmabteilung) in 1934.

After a period of incarceration in several labour camps, hiding out in forests, and being forced to choose sterilisation over deportation to a concentration camp, Rukeli was eventually drafted into the Wehrmacht in 1939 with the outbreak of war and sent to the Eastern Front. In February 1941, Roma and Sinti were discharged from the Wehrmacht on racial grounds and in July 1942, Rukeli was arrested by the Gestapo at his family home in Tiefental. He was held and severely tortured in the local police station until October 1942, when he was transported to the Neuengamme Concentration Camp near Hamburg.

While doing hard labour in gruelling 12-hour shifts, he was spotted by SS officer and former boxing referee, Albert Lütkemeyer, who forced the malnourished and exhausted Rukeli to fight his soldiers every night. In 1944, he was transferred to the Wittenberge Satellite Camp where he was again recognised and challenged to a fight by a much-hated Kapo, Emil Cornelius. Despite his condition Rukeli won the fight, but, in an act of revenge while on a work detail, the Kapo attacked him from behind and beat him to death with a shovel. His body was buried in a mass grave and never recovered.

Rukeli the Boxing Great

I’d known about the boxer nicknamed ‘Rukeli’ for many years as a symbol of antifascist resistance, but only recently did I rediscover him not just in terms of this legacy but as an athlete and professional boxer. After first stepping into a boxing ring at the age of 8, Rukeli had boxed his way up through Hannover’s working-class boxing gyms BC Heros-Eintracht and BC Sparta Linden. Despite winning the Regional Championship four times, and the title of the North German Championship, Rukeli was passed up for the 1928 Amsterdam Olympics by the German Boxing Union in favour of one of his opponents who he had defeated several times.

Undeterred, he hired Berlin manager Ernst Zirzow and in 1929, at the age of 22, Rukeli went pro. In his early career, Rukeli’s combination of heavy punches, technical proficiency, and his trademark fleet-footed ‘dancing style’ won him a string of big fights. He defeated fighters like the German Willy Bolze (KO, 4th round), Dutchman Rienus de Boer (victory by points), and Argentine Onofrio Russo (KO, 2nd round). Before the Nazis took power in January 1933, Rukeli had the making of a boxing superstar in Germany – precisely because of his exciting new fighting style. From the sound of it, Rukeli would nowadays be considered a typical out-fighter (also known as a stick-and-move fighter). This style was being developed simultaneously in the United States and elsewhere but was mostly alien to Europe in the early 20th Century. Out-fighters like Rukeli rely on fast hands, a long reach, and their ‘ringcraft’ of nimble footwork and feints to wear an opponent down while throwing jabs from outside of their reach and hard-hitting counterpunches as the opponent comes in to attack.

It’s difficult to see how Rukeli could have effectively emulated boxers developing this style in the United States considering his modest background and the technological limitations of the time. While fights were sometimes filmed, and even broadcast, their range did not cross the Atlantic. Not only for technological reasons, but fights between local boxers were mostly transmitted to very local audiences in the early 20th century. The 1937 World Heavyweight Title fight in New York between Welsh Boxer Tommy ‘the Tonypandy Terror’ Farr and the ‘Brown Bomber’ Joe Louis was probably the first boxing match televised live to a European audience.

It seems likely that Rukeli forged his dancing footwork style organically to make the most of his natural physical advantages. Had he not been born when and where he was, his name might be remembered alongside other early pioneering greats of modern pugilism. Many of these names are as much remembered for their anti-racist activism as their prowess in the ring, boxers like Archie Moore, Joe Louis, or Jack Johnson. Fittingly, the out-boxer style Rukeli was unwittingly emulating is probably most famously exemplified by another towering boxing giant and a modern symbol of anti-racist defiance: Muhammad Ali.