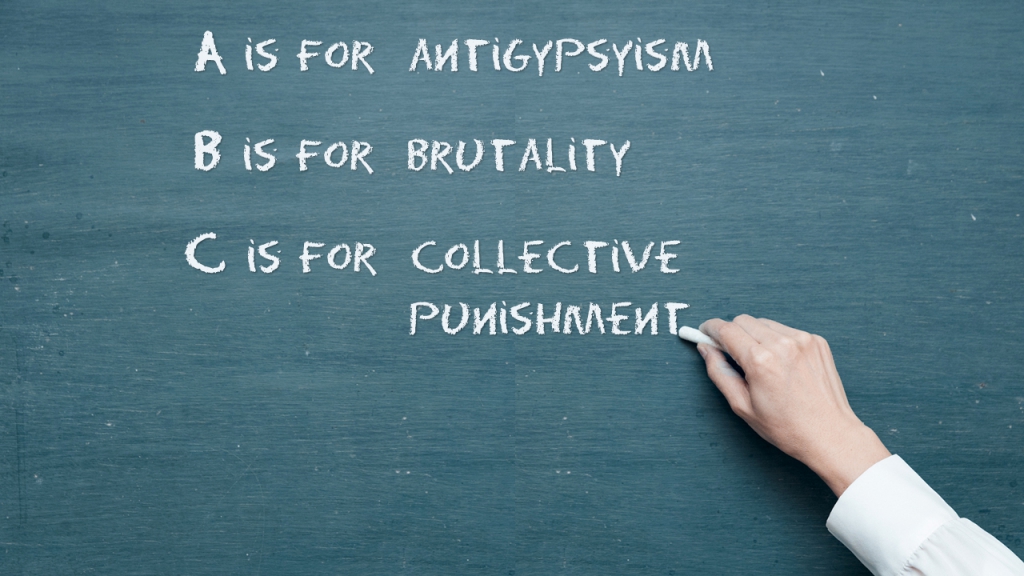

Teaching Judges their ABCs

07 January 2020

A is for Antigypsyism

“As a result of their turbulent history and constant uprooting, the Roma have become a specific type of disadvantaged and vulnerable minority”.

-The European Court of Human Rights (a bunch of times)

What a godawful sentence. Imagine tracing your family’s history through genocide, abuse, and alternating waves of forced integration and forced exclusion. “Our turbulent history?” Like the weather hit you or something. Except, actually, it was Nazis (original and neo-), police, ministers, mayors, journalists, and the everyday people who don’t want to know you exist, unless it’s so they can beat you down. “Our constant uprooting?” Who does all that uprooting?

And what’s with the “the” in “the Roma”? It is fine just to say “Roma”. Putting a “the” there is all about othering. It’s what Donald Trump does to minorities in the USA.

Yet this is the go-to phrase of the European Court of Human Rights to describe the situation of Romani people. They don’t seem to want to use the term, widely accepted by other European institutions, to describe what is going on: antigypsyism. (When we asked them to, in a case decided last year, they said “They [the ERRC] referred to so-called antigyspsyism”. The “so-called” is like that baggie you put in your hand to pick up your dog’s poo from the street, wrapping it safely and tossing it.)

Words matter. “Turbulent history” and “constant uprooting” make it sound like it’s nobody’s fault – just Roma and the weather, or something. “Antigypsyism” puts the problem where it is: non-Roma, many of whom harbour (and even more of whom benefit from) an ideology of hatred that perpetuates exclusion.

Antigypsyism forces non-Roma to define themselves, distance themselves, and show they aren’t contaminated by it. Right now politicians in the UK are squirming because they can’t escape the taint of antisemitism or Islamophobia. Politicians all over Europe should be squirming to escape the taint of antigypsyism.

B is for (Police) Brutality

Americans came up with the term “police brutality” in the late nineteenth century to describe what police officers do when they abuse their authority to beat up people (very, very often people of colour). It’s also a term we want and need to get judges using, for obvious reasons. But let’s move on. Because the letter of the day, today, is C.

C is for Collective Punishment

Lawyers and judges, if they read this, will sigh and give up around now.

“Collective punishment” (“collective penalties” to be precise) is a legal concept enshrined in the Geneva Conventions about the laws of war. And the vast majority of Roma are not living through a war right now. So, they’ll say, it doesn’t apply. Stick to “discrimination”.

But we are insisting on using it. I’m supposed to support my colleagues by telling them what the law says. So shouldn’t I tell them not to say “collective punishment”?

No. Because my colleagues are on to something. Article 33 of the Fourth Geneva Convention says this: “No protected person may be punished for an offence he or she has not personally committed”. Legally, this is about civilians in wartime. But what would you call it when:

- someone in your racially segregated Romani neighbourhood is accused of dealing drugs and the local council votes to expel all Roma from the village? (Ukraine)

- the police are trying to arrest someone who was on weekend release from prison and didn’t come back, so they send in dozens of heavily armed officers who start beating up everyone in sight? (North Macedonia)

- the cops use a special “action code” for violent raids that somehow always seem to hit Romani neighbourhoods? (Slovakia)

- an off-duty cop takes his police-issued gun, goes to a Romani neighbourhood, and shoots at a Romani family in their front garden, because he needed to “do something”? (Slovakia)

- tens of thousands of Roma are evicted from their homes each year, while ministers tell the public that Roma should be “delivered back to the borders” (France)

Collective punishment – the racist impulse to inflict suffering on large numbers of Roma for alleged (often invented or exaggerated) offences by one or a few Romani people – is a classic, enduring feature of antigypsyism.

We need to start calling these things what they are. It isn’t “turbulent”. It isn’t even “history”. It’s now and it dehumanises Romani people by assuming that all Roma should suffer because one or more Romani people may have done something wrong.

C is also for Complain

Roma were collectively punished in wartime, of course – in World War II and again in the 1990s in disintegrating Yugoslavia. On 16 May Roma celebrate Romani Resistance Day – a violent fight back against the Nazis’ genocide.

What does fighting back look like now?

At the ERRC, we think it means turning the force of collective punishment back on the racists. That means turning collective punishment into mass complaints. If the police beat up 100 people to arrest one, then 100 people have a complaint to the police oversight body. When 200 people are chased out of their homes by a racist mob, 200 people have a discrimination claim for losing their homes and possessions.

This takes guts. The perpetrators of collective punishment are powerful people. But they are also cowards. Right now, they are taking advantage of the silence they impose on their victims – meaning almost no cases of collective punishment reaching the courts. And they are taking advantage of the fact that their intimidation tactics mean only a few Romani people can step up.

Romani resistance means a critical mass of these complaints. So many that they force the people receiving the complaints – civil courts, police oversight bodies, equality bodies (sometimes called commissioners for protection against discrimination), data protection authorities, prosecutors – to stop and say “What the f*** is going on?”

Let’s not kid ourselves. The people who make decisions in these bodies swim in the same contaminated lake of antigypsyism as the mayors and cops and ministers who perpetrate collective punishment. What will shock the judge or the prosecutor or the equality commissioner is not that this is happening, but that they have to deal with it, and call on someone to answer for it. They are counting on victims’ silence like everyone else. It makes their lives easy.

The ERRC’s challenge in 2020 is how to break the silence that comforts racists after they collectively punish Romani people. We don’t have easy answers. We need to talk to people about what will make it possible for 50 or 500 people to stand up and complain. It won’t always be possible. But sometimes it will.

It will blow the minds of the assholes who mastermind violent police raids, pogroms, and evictions. And let’s hope it will get some of them fired.

Because that’s the only way you can teach some people.

From the Winter 2019 edition of the ERRC Roma Rights Review, click here to see more.