Why don't bystanders intervene to stop racist attacks?

26 November 2020

By Milena Ćuk

On October 1st, a dramatic scene took place on the 706 public bus in Belgrade, when a Romani couple were brutally beaten by a young guy in a racist attack.

On a bus full of people, nobody reacted when he started beating the Romani couple to the ground except one person: Milica, a 26-year-old woman on her journey home.

Milica intervened and did the only thing she could do, she shouted and persuaded the driver to stop when she saw police officers at the next bus station. When the bus stopped she was again the only one helping the couple exit the bus and the only one ready to give a statement to the police as a witness to the disturbing scene. Later, she was the only one ready to fight for justice by sharing her experience publicly on Facebook, drawing the attention of the wider public, media and human rights defenders.

What happened on that bus in Belgrade, and all the events that followed, is a representative image of Serbian society today. There are bullies of different kinds (persons, groups or institutions), there are victims, and there are folks that keep silent. Sometimes those who keep silent are even the same ones who are the target. Frequently there is just not enough will or strength from those involved to react.

What Milica did, as a symbolic act of resistance, breaks this pattern. She refused to keep silent and used her voice to call out the injustice which everyone else was ignoring. But why did no one else do what Milica did? We may find some answers by looking at this case from a psychological perspective.

How can we explain the passivity of the bystanders?

Why do people keep silent in an unjust situation? Is it possible just to turn away from another person’s anguish happening in front of your eyes? How can we explain the fact that, except for Milica, nobody else on the bus got involved when the attack happened, or later to help the victims, or at least to help them seek justice afterwards?

Fear

Feeling fear in a threatening situation such as a violent attack and becoming frozen is a natural reaction. An aggravating factor in this situation was the fact that there was no place to run away or to hide from a furious attacker if he moved his focus to the one who was reacting.

Racist attitudes and lack of empathy to the victims

Like elsewhere in Europe, stereotypes and prejudices against Roma in Serbia are very high. Moreover, the current political situation in the country is ripe for increased intolerance and hatred towards those we consider as other to the mainstream society, including Roma as one of the least tolerated communities here.

Milica described how she saw passengers helping the attacker with advice on where to get away from the police when the bus stopped. How can you “cheer” a bully if not because he targets those who you don’t like and got what they deserved according to your beliefs? I suppose that if the victims in this case were not Roma, someone else would have joined Milica; at least helped them to exit the bus.

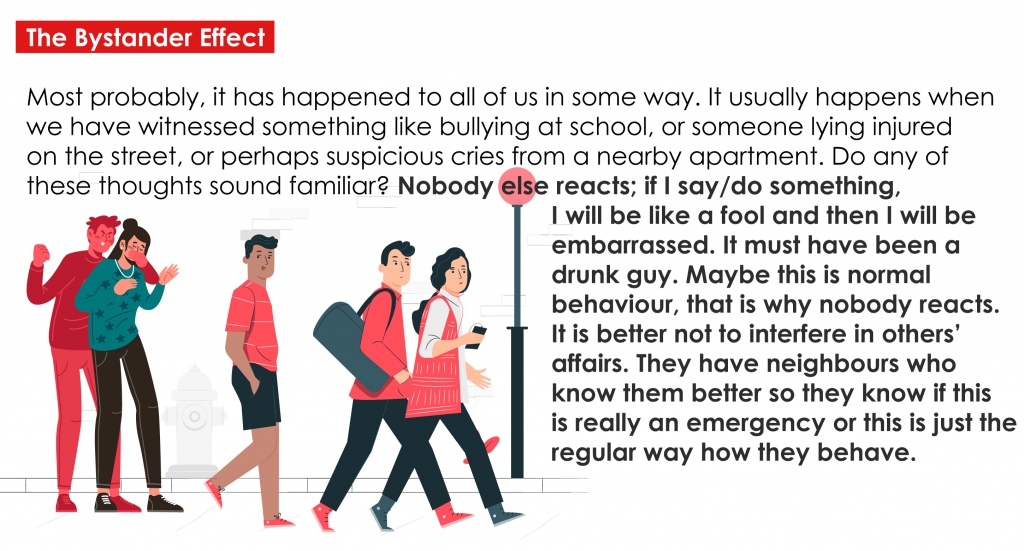

“The Bystander effect”

A phenomenon investigated a lot in social psychology, the Bystander Effect refers to a phenomenon of hesitating or deciding not to intervene in a situation where there is somebody who needs help in the presence of a crowd or a few other people. It usually occurs in a public space such as the street, public transport, or a market. The person who needs help may be being attacked by someone or in some other difficulty, for instance somebody who fainted, suffered a heart attack or similar.

Two years ago, the Serbian public were disgusted by a video filmed on a public tram where a guy was obviously sexually harassing a minor girl. There were at least three women witnessing the scene, sitting very near the girl, but they didn’t do anything to help her. Here, the victim was a “white” child and it was expected that the majority would empathise – but again, the reaction was missing.

It is established that the presence of other people influences somehow our readiness to react. When we are aware that there are other bystanders in an emergency situation in public, we tend to think: Oh, there are other people, somebody else will react. Or: This is not my responsibility, why would I react; there are more competent or stronger people who will do something about it.

This factor related to the bystander effect is called Diffusion of responsibility. Another important factor related to this tendency not to react is called Social influence, meaning that we tend to pay attention to the behavior of other bystanders around us in order to determine how to react. We fear that our reaction will be perceived as foolish and we will feel embarrassed.

“Learned helplessness”

The question of passivity has been bothering me for a long time time because I see it every day. It is so common here in Serbia that it seems like it became something of a collective trait. People are not satisfied. They are suffering, they don’t approve of something, they are complaining; but in the majority of cases they choose not to react, not to change the status quo. When they gather the energy to do something, they often quit after the first few obstacles.

Being trapped in a passive position is associated with the belief that one cannot actually change anything, so it is pointless to try. Deep down, one feels helpless. This perception of lacking control over the situation and consequently feeling helpless inspired American psychologist Martin Seligman to coin the term learned helplessness when he was researching depression.

Passive behaviour (not reacting, nor participating) in Serbia is part of the legacy of our communist past and a dominant subject political culture. In the past, citizens were heavily subjected to the central government’s decisions with little scope for dissent. To put it simply, for decades it has been encouraged that people give up their ability to think and to act in favour of a State (read: Party) that thinks and acts for them. Better keep your mouth shut than to put yourself in a worse situation is a message that passes from generation to generation, and there’s been a logical reason for that - people who openly have expressed their opinion have normally been punished for it.

We have a similar trend nowadays, but despite this, there have always been people with a free mind and spirit who fight for democracy. Unfortunately they are a minority at the moment, and changing a system is a very slow process.

Why is Milica’s act so important in Serbia today?

It is evident that we are faced with rising violence at all levels in society, and that hatred and intolerance to those perceived as other is flourishing.

This violence originates from the toxic narratives and hate speech which poisons our public discourse, dividing our society into us and them. Under these conditions it is unsurprising that it often escalates into violent outbursts, especially against certain groups that are targets for venting suppressed rage and hatred: Roma, migrants, political opponents, and all others perceived as a threat to the current order.

This is exactly why Milica’s act is important since it shows refusal of the “ordinary” citizen to follow the current trends of dividing people, of staying in the helpless position and not reacting to injustice.

So what can we, as ordinary citizens, learn from Milica's actions?

We should remind ourselves again and again to react out of conscience. Especially in the context of an increasingly authoritarian and hostile political environment, it is important not to forget to be a human. That is why Milica’s act has a symbolic value; to remind us and inspire us to do what we feel is the right thing to do in an unjust situation.

If we find ourselves beginning to subscribe to the belief that our individual acts are pointless, we should ask ourselves: How did I get to the point where I have given away my personal power and ability to actively participate in the world around me? Our small actions may not change the world, but they can comfort and inspire others.

If we are afraid, we can think if there are ways to react without jeopardizing our own safety. For instance, calling the police; shouting from a distance: Stop!; What is going on?; Police are coming; or offering to give help or a statement afterwards.

Secondly, we shouldn’t wait for others to take responsibility but should decide to take action first. If we are reluctant, we may ask ourselves: if there were no other bystanders, how would I react? If the victim of the attack was my loved one – my child, brother, sister, father, mother - would I just stand waiting for the attacker to calm down or help to come from somebody else?

Remember that it can happen to all of us that we are attacked just because we are perceived as a threat, different or just as an “easy” target. Most probably, the attacker is themselves not immune to the social pressures of a crowd, so the chances to cease violent acts are higher if more bystanders intervene.

Finally, perhaps the most symbolic value of Milica's act is the fact that she, as a non-Roma woman, stood up to help Roma. It doesn’t happen so often. We can learn from her example and rise above these artificial and ruinous divisions of “us” and “them” that lead only to destruction and suffering. We are all together in this mess and only with solidarity can we get out of it.